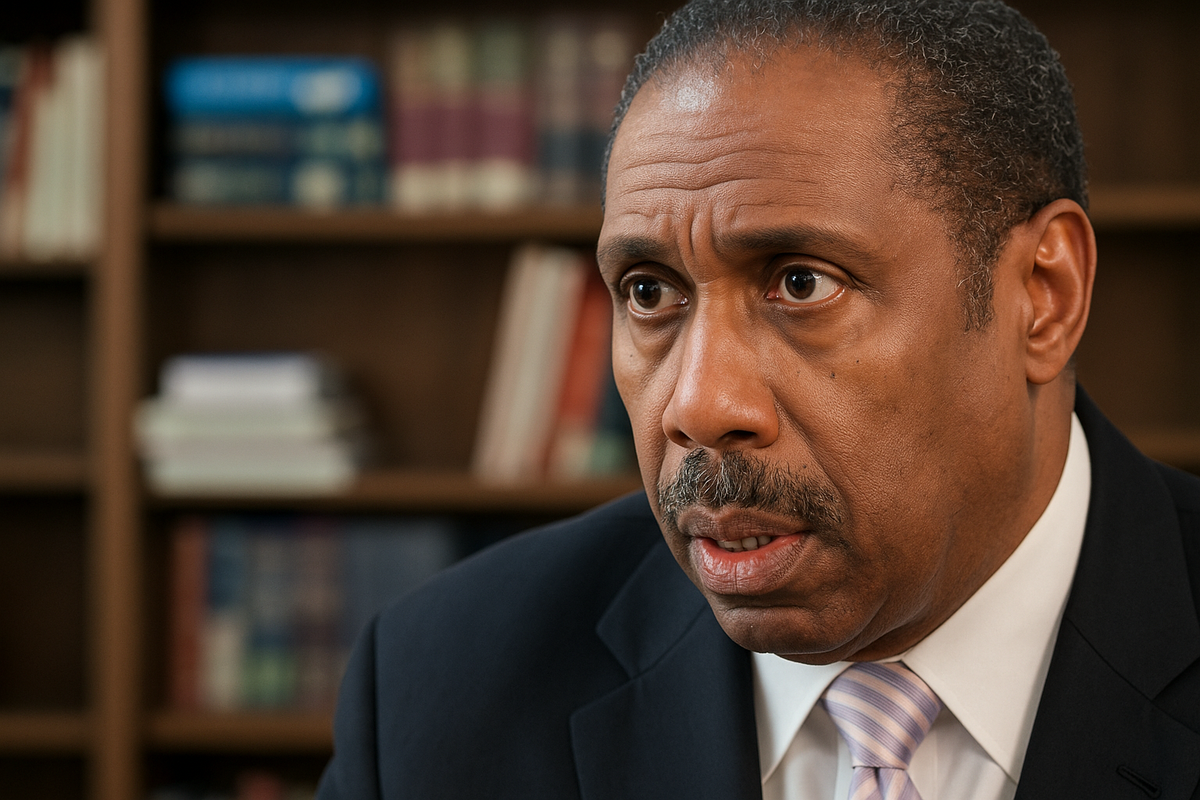

Dr. Jawanza Kunjufu: An Appreciation

Perhaps not as well known as many in the activist communities, he still had just as much of an impact.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about my experience with my fourth-grade teacher, who to this day remains on my Mount Rushmore of awful people I have known in my life. She was an excellent example of how a single schoolteacher can work to derail the educational trajectory of Black boys, making them liquid in the school-to-prison pipeline.

Fortunately, she didn’t turn out to be the negative factor in my life that she likely intended to be, but there is someone who advocated for better standards for teaching Black children. Sadly, we recently lost him, a true giant: Dr. Jawanza Kunjufu. He was 71 and passed away on April 21, according to his website, African American Images.

Best known for his book, “Countering the Conspiracy to Destroy Black Boys,” beginning in the mid-1970s, Kunjufu was among the few people to examine how the educational system was impacting Black males. The groundbreaking work, whose first volume was released in 1983, examined what caused many Black boys to fall off their educational trek. He refused to believe that they were less intelligent or inferior, despite such stereotypes surviving as standard thought for centuries.

He wrote in a 2005 forward to a collection of his “Conspiracy” series:

I have often been asked why I concentrate more on boys than men. I have believed over the past two decades that the problems African American men are experiencing did not begin when they were incarcerated at 21 years of age. I don’t believe the problem men have keeping their word, showing up for work on time, and raising their children began in adulthood.

To Kunjufu, the time to deal with issues among Black men is not when they have grown and the damage is done, it’s when they are boys and can be guided and nurtured by responsible people who care about their development. In this video below, made in 1987, he outlines this masterfully.

It relates to the point I made in my essay when I spoke about the lack of Black men attending college. Again, we are discussing Black men missing out on higher education ten years too late. The time to focus on moving toward college or skills training is when they are kids.

A Chicago native, Kunjufu earned his degrees in economics and business administration, but what was happening to Black students caught his interest early on during a time when much thought was being given to how systemic racism was entrenched in the educational system, and a generation of teachers who had come through the Civil Rights and Black Identity movements began to take over classrooms.

In those years, more contemporary authors like James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni, and Maya Angelou were being added to curricula along with Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, and Negro History Week had transformed into Black History Month. As children, we witnessed the conservative even-temperedness of Jackie Robinson transforming into the radical vocality of Muhammad Ali, and the clean-cut smoothness of Marvin Gaye in the 1960s singing “If This World Were Mine” becoming his raw, unfiltered cry of “What’s Goin’ On” in the 1970s.

Thus, more scrutiny of the educational system when it came to Black children emerged, and it was in this environment that Kunjufu arrived. He began a journey of educational consulting and research techniques used with Black students, along with being the author of 65 books and founder of Chicago-based African American Images.

In his work, he discovered that contrary to established understanding, the problems were with the system and not the children.

“Normally, school districts bring me in to ‘fix the bad Black students.’ They either bring me in because there is a problem with low test scores, because of disciplinary issues or suspensions,” he told Diverse Issues in Higher Education in 2012. “The assumption from the superintendent or the principal is that there’s really nothing wrong with the environment (within the school), and especially in a school district where in the good old days — five, 10, 15, 20 years ago — when the neighborhood was predominantly white, those same teachers were very successful with white middle-class students, so it has to be something wrong with these students.

“What I have done over my career is that I have challenged teachers, ‘Should we in an educators workshop [to] look at parents for what they are not doing between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m.?’ Or should we with the existing people in this room, [asking] ourselves, ‘Is there anything we can do better between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m.?’”

In addition to the four-volume “Conspiracy” series, which was published between 1983 and 1995, Kunjufu’s writings also focused social currency with “To Be Popular or Smart” (1988); sexuality and relationships with “The Power, Passion and Pain of Black Love” (1993) and “Good Brothers Looking for Good Sisters” (1997); and pushing back against conventional assumptions about the racial achievement gap in “There is Nothing Wrong With Black Students.” (1993).

I personally became aware of Kunjufu’s work when I was in college and he visited my campus in the early 1990s. I remember him talking even then about the gap between men and women at the school, and he told us that the uneven ratio was not our fault, and praised us for being there and pursuing education against incredible odds. I was a fan from then on.

Perhaps he was not as popular as the more well-known activists like Rev. Jesse Jackson or Rev. Al Sharpton, but his work was just as impactful because it was more focused and direct.

In 1988, Kunjufu appeared on a local Bay Area show with writer and scholar Ishmael Reed and Black Panthers founder Huey Newton in what would turn out to be his final public appearance. They were there for a Martin Luther King Jr. holiday episode to discuss the image of Black men, and the show couldn’t have been more poorly conceived or more exploitative. But while Newton and Reed were scrutinized by the two detached hosts, Kunjufu shined as he described how the educational system disenfranchises Black boys.

It was truly a blessing to have him, and we are better for it. Rest in power, Brother Jawanza.

Madison Gray is a New York City-based writer and editor whose work has appeared in multiple publications globally. Reach out to him at madison@starkravingmadison.com.